Getting started with NativeJIT

NativeJIT is a just-in-time compiler that handles expressions involving C data structures. It was originally developed in Bing, with the goal of being able to compile search query matching and search query ranking code in a query-dependent way. The goal was to create a compiler than can be used in systems with tens-of-thousands of queries per second without having compilation take a significant fraction of the query time.

Let’s look at a simple “Hello, World” and then look at what the API has to offer us.

Hello World

We’re going to build a function that computes the area of a circle, given its radius. If we were to write such a function in C, it would look something like

const float PI = 3.14159;

float area(float radius)

{

return radius * radius * PI;

}

Building this function in NativeJIT involves three steps: creating a Function

object which defines the function prototype, building the expression tree which

defines the function body, and finally compiling the function into x64 machine

code.

Create the Function Object

The Function constructor takes one to five template parameters and exactly two regular parameters. The template parameters define the function prototype, while the regular parameters supply resources necessary to compile and run x64 code.

Template Parameters

The template parameters define the function prototype for the compiled code. The first parameter defines to the return value type. The remaining template parameters correspond to the function’s parameter types.

For our example, we’re defining a function that takes a single float parameter

for the radius and returns a float area, so our template parameters would be

<float, float>.

Function<float, float> expression(allocator, code);

Allocator

The allocator provides the memory where expression nodes will reside. Any class

that implements the IAllocator interface will do.

A reasonable default is to use the arena allocator provided in NativeJIT’s

Temporary directory. The arena allocator hands out blocks of memory from a

fixed size buffer. All of this memory can be recycled at once by calling the

allocator’s Reset() method. The advantage of the arena allocation pattern is

that it allows you to quickly dispose of an expression tree after

compilation. The disadvantage is that it requires everything that uses the

allocated memory to be aware that it’s using an arena allocator.

The constructor for allocator takes a single parameter which is the buffer size in bytes.

Allocator allocator(8192);

FunctionBuffer

The FunctionBuffer provides the executable memory where the compiled code will

reside. In order to allow code execution, this memory must have Executable

Space Protection

disabled.

NativeJIT provides the ExecutionBuffer class which is an IAllocator that

allocates blocks of executable code. Classes starting with I are interfaces,

so this is saying that ExecutionBuffer satisfies the IAllocator

interface. Its constructor takes a single parameter which specifies its buffer

size. Note that the buffer size will typically be rounded up to the operating

system virtual memory page size since the NX

bit is applied at the page level.

The FunctionBuffer constructor takes an ExecutionBuffer and a buffer size.

The buffer size parameter might seem redundant given that

the ExecutionBuffer takes a buffer size as well. The reason the

FunctionBuffer constructor takes a buffer size is that multiple

FunctionBuffers can share a single ExecutionBuffer.

Here’s the code fragment:

ExecutionBuffer codeAllocator(8192);

FunctionBuffer code(codeAllocator, 8192);

Function<float, float> expression(allocator, code);

Build the Expression Tree

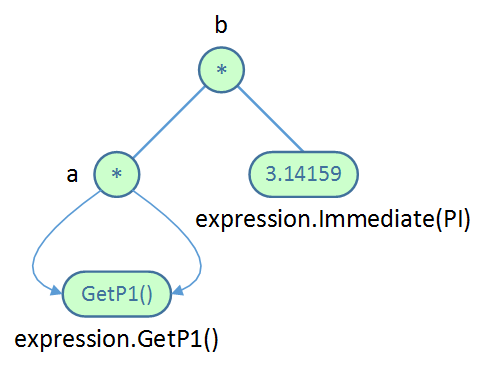

The next step is to build the expression tree which defines the function body. In the expression tree, interior nodes are operators and the leaf nodes are either literals or function parameters.

The tree is built from the bottom up.

Function<float, float> expression(allocator, code);

const float PI = 3.14159265358979f;

auto & a = expression.Mul(expression.GetP1(), expression.GetP1());

auto & b = expression.Mul(a, expression.Immediate(PI));

In the code above, expression.GetP1() is a leaf node corresponding to the first parameter.

Node a is defined to be the product of the first parameter with itself.

On the next line, expression.Immediate(PI) is an immediate value leaf node whose value is equal to PI.

Node b is defined to be the product of node a and PI.

Note that each of the node factory methods on Function is templated by the types of its children.

This is an important safeguard the prevents the construction of a tree with type errors

(e.g. adding a double to a char).

Compile

Once the tree is built, it’s time to generate x64 machine code:

auto computeRadius = expression.Compile(b);

The compiler returns a pointer to the compiled function.

In this example, its type is float (*)(float).

Run

You call this just like calling a C function!

auto result = computeRadius(radius_input);

Putting it all together

#include "NativeJIT/CodeGen/ExecutionBuffer.h"

#include "NativeJIT/CodeGen/FunctionBuffer.h"

#include "NativeJIT/Function.h"

#include "Temporary/Allocator.h"

#include <iostream>

using NativeJIT::Allocator;

using NativeJIT::ExecutionBuffer;

using NativeJIT::Function;

using NativeJIT::FunctionBuffer;

int main()

{

ExecutionBuffer codeAllocator(8192);

Allocator allocator(8192);

FunctionBuffer code(codeAllocator, 8192);

const float PI = 3.14159265358979f;

Function<float, float> expression(allocator, code);

auto & a = expression.Mul(expression.GetP1(),

expression.GetP1());

auto & b = expression.Mul(a, expression.Immediate(PI));

auto function = expression.Compile(b);

float p1 = 2.0;

auto expected = PI * p1 * p1;

auto observed = function(p1);

std::cout << expected << " == " << observed << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Examining the x64 Code

If you’re interested in seeing the x64 code,

fire up the debugger and set a breakpoint

on a line after the code has been compiled,

for example the line float p1 = 2.0.

Then get the value of function, and switch into

disassembly view, starting at this address.

Here’s what you should see on Windows.

sub rsp,8 ; Standard function prologue.

mov qword ptr [rsp],rbp ; Standard function prologue.

lea rbp,[rsp+8] ; Standard function prologue.

mulss xmm0,xmm0 ; Radius parameter by itself.

mulss xmm0,dword ptr [29E2A580000h] ; Multiply by PI.

mov rbp,qword ptr [rsp] ; Standard function epilogue.

add rsp,8 ; Standard function epilogue.

Linux output may look slightly different because of differences in the ABI.

On Windows you can single step through the generated code in the debugger. Because NativeJIT does not implement x64 stack unwinding on Linux and OSX, you may have trouble single stepping through the generated code, but it will run correctly.

Rules of the Road

For the most part, NativeJIT assumes that the entire expression tree is free of side effects.

The only general purpose node that can cause a side effect is CallNode which calls out to an external function.

The behavior of the generated code is undefined when calling out to external functions that cause side effects.

In the current implementation, each node will be evaluated exactly once. This guarantee is an important optimization that holds for common subexpressions. These are nodes that have multiple parents.

Common subexpressions often show up when traversing data structures. In the following example

foo[i].bar.baz + foo[i].bar.wat

the expression foo[i].bar is a fairly complicated subexpression

involving multiplication, addition, and a pointer dereferencing.

Since it is a common subexpression, this work will only be done once.

NativeJIT provides an experimental ConditionalNode analogous the the

ternary conditional operator in C.

Today the generated code evaluates both the true branch and the false branch,

independent of the value of the conditional expression.

Down the road we intend to rework the code generator to

restrict execution to either the true or the false path.

Today the register allocator makes assumptions about register spills

and temporary allocations in both branches, and these assumptions must

be carried forward through all code that is executed after the first

conditional branch.

It’s important to take into account whether the code will run locally. For example, if you’re running JIT’d code locally, it is legal to use the address of a C symbol as a literal value. If you are JITing on run machine and executing code on another be aware that there’s guarantee that the symbol will be at the same address on another machine.

This scenario typically comes up when attempting to call out to

external functions. The solution is to have the caller pass the

address in as a parameter of the compiled code, instead of relying

on a function address in an ImmediateNode.

As mentioned earlier, NativeJIT only implements x64 stack unwinding on Windows. Aside from the debugging impact mentioned above, the other risk in omitting stack unwinding is that an exception thrown from a C function called from NativeJIT code may not be caught properly on Linux and OSX.

If you grep for DESIGN NOTE in the code, you can find explanations of other quirks in NativeJIT.

Commonly used methods

Immediates

These are simple types (e.g., char or int) or pointers to anything. This means that we can have, for example, pointers to structs but we can’t have struct literals.

template <typename T> ImmediateNode<T>& Immediate(T value);

Examples

// Immediate.

Function<int64_t> exp1(allocator1, code1);

auto &imm1 = exp1.Immediate(1234ll);

auto fn1 = exp1.Compile(imm1);

assert(1234ll == fn1());

Unary Operators

template <typename TO, typename FROM> Node<TO>& Cast(Node<FROM>& value);

Pointer dereference; basically like *:

template <typename T> Node<T>& Deref(Node<T*>& pointer);

template <typename T> Node<T>& Deref(Node<T*>& pointer, int32_t index);

template <typename T> Node<T>& Deref(Node<T&>& reference);

Field de-reference; basically like ->. If you have a, and apply the b FieldPointer, that’s equivalent to a->b. There’s no . because we don’t have structs as value types.

If you have a reference to an object, you have to convert the reference to a pointer to apply this method. Note that this has no runtime cost.

template <typename OBJECT, typename FIELD, typename OBJECT1 = OBJECT>

Node<FIELD*>& FieldPointer(Node<OBJECT*>& object, FIELD OBJECT1::*field);

Because we have some operations that can only be done on pointers (or only done on references), we have AsPointer and AsReference to convert between pointer and reference. This is free in terms of actual runtime cost:

template <typename T> Node<T*>& AsPointer(Node<T&>& reference);

template <typename T> Node<T&>& AsReference(Node<T*>& pointer);

Examples

// Cast.

Function<int64_t> exp1(allocator1, code1);

auto &cast1 = exp1.Cast<float>(exp1.Immediate(10));

auto fn1 = exp1.Compile(cast1);

assert(float(10) == fn1());

// Access member via ->.

class Foo

{

public:

uint32_t m_a;

uint64_t m_b;

};

Function<uint64_t, Foo*> expression(allocator2, code2);

auto & a = expression.GetP1();

auto & b = expression.FieldPointer(a, &Foo::m_b);

auto & c = expression.Deref(b);

auto fn2 = expression.Compile(c);

Foo foo;

foo.m_b = 1234ull;

Foo* p1 = &foo;

assert(p1->m_b == fn2(p1));

Binary Operators

Binary artihmetic ops take either two nodes, or a node and an immediate. Note that although the types are templated as L and R, L and R should generally be the same for binary ops that take two nodes – conversions must be made explicit. For Rol, Shl, and Shr, the immediate should be a uint8_t.

template <typename L, typename R> Node<L>& Add(Node<L>& left, Node<R>& right);

template <typename L, typename R> Node<L>& And(Node<L>& left, Node<R>& right);

template <typename L, typename R> Node<L>& Mul(Node<L>& left, Node<R>& right);

template <typename L, typename R> Node<L>& Or(Node<L>& left, Node<R>& right);

template <typename L, typename R> Node<L>& Sub(Node<L>& left, Node<R>& right);

template <typename L, typename R> Node<L>& Rol(Node<L>& left, R right);

template <typename L, typename R> Node<L>& Shl(Node<L>& left, R right);

template <typename L, typename R> Node<L>& Shr(Node<L>& left, R right);

Like [], i.e., takes a pointer and adds an offset:

Node<T*>& Add(Node<T(*)[SIZE]>& array, Node<INDEX>& index);

template <typename T, typename INDEX> Node<T*>&

Add(Node<T*>& array, Node<INDEX>& index);

Examples

// Array dereference with binary operation.

Function<uint64_t, uint64_t*> exp1(allocator1, code1);

auto & idx1 = exp1.Add(expression.GetP1(),

expression.Immediate<uint64_t>(1ull));

auto & idx2 = exp1.Add(expression.GetP1(),

expression.Immediate<uint64_t>(2ull));

auto & sum = exp1.Add(expression.Deref(a), expression.Deref(b));

auto fn1 = exp1.Compile(sum);

uint64_t array[10];

array[1] = 1;

array[2] = 128;

uint64_t * p1 = array;

assert(array[1] + array[2] == fn1(p1));

Compare & Conditional

Unlike other nodes, which return a generic T, compare nodes return a flag. The

flag can be passed to a conditional, which takes a flag.

FlagExpressionNode<JCC>& Compare(Node<T>& left, Node<T>& right);

template <JccType JCC, typename T>

Node<T>& Conditional(FlagExpressionNode<JCC>& condition,

Node<T>& trueValue,

Node<T>& falseValue);

template <typename CONDT, typename T>

Node<T>& IfNotZero(Node<CONDT>& conditionValue,

Node<T>& trueValue,

Node<T>& falseValue);

template <typename T>

Node<T>& If(Node<bool>& conditionValue,

Node<T>& thenValue,

Node<T>& elseValue);

x86 conditional tests are available; a full list is available here.

Example

// JA (jump if above), i.e. unsigned ">"

Function<uint64_t, uint64_t, uint64_t>

exp1(setup->GetAllocator(), setup->GetCode());

uint64_t trueValue = 5;

uint64_t falseValue = 6;

auto & a =

expression.Compare<JccType::JA>(expression.GetP1(), expression.GetP2());

auto & b =

expression.Conditional(a,

expression.Immediate(trueValue),

expression.Immediate(falseValue));

auto function = expression.Compile(b);

uint64_t p1 = 3;

uint64_t p2 = 4;

auto expected = (p1 > p2) ? trueValue : falseValue;

auto observed = function(p1, p2);

assert(expected == observed);

p1 = 5;

p2 = 4;

expected = (p1 > p2) ? trueValue : falseValue;

observed = function(p1, p2);

assert(expected == observed);

Call

Calls a C function.

template <typename R>

Node<R>& Call(Node<R (*)()>& function);

template <typename R, typename P1>

Node<R>& Call(Node<R (*)(P1)>& function,

Node<P1>& param1);

template <typename R, typename P1, typename P2>

Node<R>& Call(Node<R (*)(P1, P2)>& function,

Node<P1>& param1,

Node<P2>& param2);

template <typename R, typename P1, typename P2, typename P3>

Node<R>& Call(Node<R (*)(P1, P2, P3)>& function,

Node<P1>& param1,

Node<P2>& param2,

Node<P3>& param3);

template <typename R, typename P1, typename P2, typename P3, typename P4>

Node<R>& Call(Node<R (*)(P1, P2, P3, P4)>& function,

Node<P1>& param1,

Node<P2>& param2,

Node<P3>& param3,

Node<P4>& param4);

Examples

// Call SampleFunction.

int SampleFunction(int p1, int p2)

{

return p1 + p2;

}

Function<int, int, int> exp1(allocator1, code1);

typedef int (*F)(int, int);

auto &imm1 = exp1.Immediate<F>(SampleFunction);

auto &call1 = exp1.Call(imm1, exp1.GetP1(), exp1.GetP2());

auto fn1 = exp1.Compile(call2);

assert(10+35 == fn1(10, 35));

Rarely used methods

Unary methods

template <typename FROM> Node<FROM const>& AddConstCast(Node<FROM>& value);

template <typename FROM> Node<FROM>&

RemoveConstCast(Node<FROM const>& value);

template <typename FROM> Node<FROM&>&

RemoveConstCast(Node<FROM const &>& value);

template <typename FROM> Node<FROM const *>&

AddTargetConstCast(Node<FROM*>& value);

template <typename FROM> Node<FROM*>&

RemoveTargetConstCast(Node<FROM const *>& value);

These sounds really weird, but they were useful for some obscure reasons.

Binary methods

Node<T>& Shld(Node<T>& shiftee, Node<T>& filler, uint8_t bitCount);

This is used for packed types (i.e., bitfields that get packed into 64-bits) to extract a bitfield.